One World

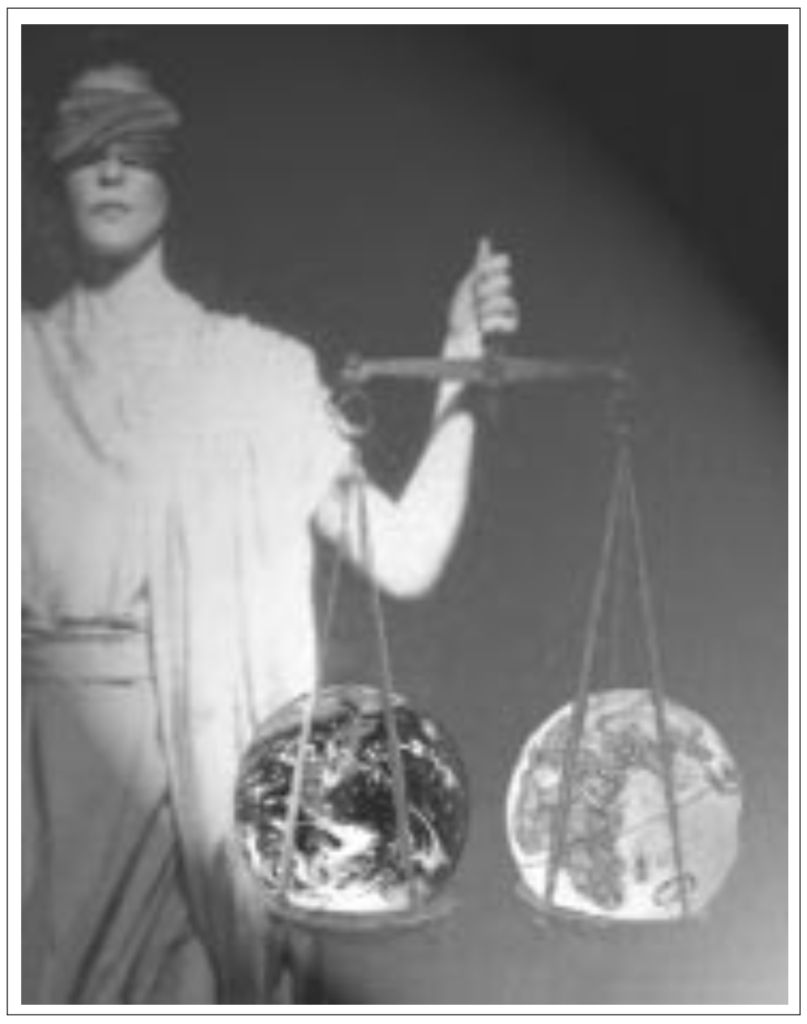

A Progressive Vision for Enforceable Global Law

Democracy

Jerry Tetalman and Byron Belitsos

Origin Press San Rafael, California

Origin Press

P.O. Box 151117, San Rafael, CA 94915 www.OriginPress.com

Copyright © 2005 by Jerry Tetalman and Byron Belitsos

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without prior written permission from the publisher.

Cover and book design by Phillip Dizick pdizick@earthlink.net

Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication

(Provided by Quality Books, Inc.)

Tetalman, Jerry. One world democracy : a progressive vision for

enforceable global law / by Jerry Tetalman and Byron Belitsos.

p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. LCCN 2005925238 ISBN 978-1-57983-017-5 ISBN 1-57983-017-X

1. International organization. 2. International relations. 3. Democratization. 4. Rule of law. I. Belitsos, Byron, 1953- II. Title.

JZ5566.4.T48 2005 341.2’1 QBI05-600045

First printing: June 2005 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ON RECYCLED PAPER

This book is dedicated to all those who are working for peace, justice, and sustainability— now and into the far future.

viii

Acknowledgements

My wife for the gift of encouragement. My daughter for the gift of belief. My mother for the gift of thinking big. My brother and sisters for the gift of staying balanced. Melvin Clay for the gift of independent thinking. Lynn Sparks for the gift of non-conformity.

Jessica Clark for the gift of teaching writing. Carrie Cantor for the gift of organization. Judy Cullins for the gift of just going for it. Jane Shevtsov for the gift of understanding. Mike, Matt and Tom Ferry for the gift of self-confidence. Jim Van Der Water for the gift of taking action.

Ann Hoiberg for the gift of helping. Byron Belitsos for the gift of teamwork. Donna Volpe for the gift of courage. Garry Davis for the gift of activism. George Marsh for the gift of saying what you mean. Phillip Dizick for the gift of being an artist. Gwen Price for the gift of precision. Lauren Dowell for the gift of kindness. Zadi Balouch for the gift of loyalty. Robin Ardez for the gift of planning. Ed Duliba for the gift of dedication. Aaron Knight for the gift leadership. Therese Tanalski for the gift of having a cause. Bill Bryant for the gift of support. John Sutter for the gift of connecting people. Antera for the gift of accomplishment. Mike Fraijo for the gift of trust.

—Jerry Tetalman

I would like to acknowledge my mentors in the world feder- alist movement, including but not limited to: Tad Daley, Bob Gauntt, and Lucile Green, as well as those who most inspired me: Garry Davis, Troy Davis, Ben Ferencz, Jerry Gerber, Pat Fearey, Roger Kotila, Steve McIntosh, and Chuck Thurston. A special thanks to John Sutter for superb editorial input, and also to the Democratic World Federalists in San Francisco, including Eric Schultz, who over the years have provided the kind of friendship and comradeship that is needed to birth a book like this. Above all, I am grateful to Jerry Tetalman, whose vision, patience, tolerance, and love of humanity made this book possible.

—Byron Belitsos

ix

Contents

Preface………………………… xv PART I

Principles of Democratic Global Governance

- The Peoples of the World Are Sovereign. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3 The ideal of “one world” was established in the 1940s Peace always grows as sovereignty expands The UN does not represent the sovereignty of humankind True sovereignty is personal and global Nations retain their identity in a world federation Sovereignty is legitimate political power—in action

- The Case for Global Law …………………….23 A simple truth: Peace requires the rule of law Legislators can quickly adapt global laws to global needs We must distinguish the causes and effects of anarchy “International law” is a misnomer Global law is meaningful only if it is enforceable Global law requires global courts of justice Enforceable world law is an idea whose time has come

- From World Citizenship to World Democracy. . . . . . . . . . . 39 We need political enfranchisement at the global level Individual accountability at the global level is an imperative Ad hoc tribunals and the ICC mark a beginning World citizenship is no longer a mere sentiment Global activism for world citizenship is needed now

- The Need for a Global Legislature…………… … 52 The grandest democratic endeavor of all time is imminent The European Parliament is a prototype for a world parliament Inspired citizens’ efforts for global democracy have already born fruit A world parliament could be launched as an autonomous body A constitutional global democracy is needed now

xi

xii

- The War System and the Wisdom of Federation. . . . . . . . . 72 The war system has an insidious effect The war system is toxic in each country World federation is the solution to the war system World federalism arose in response to World War II Federation is radically different from confederation The benefits of federation are many

- How Do We Create a World Government? . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92 Regional organizations could create a restructured UN A union of democracies is a logical place to start A worldwide constitutional convention is a plausible vehicle The EU offers a historic model of a union of nations Restructuring the United Nations is feasible and desirable A few critical reforms could transform the UN An opportunity like no other stands before usPART II Global Problems that Need Global Solutions

- Eliminating Nuclear Weapons…………………119 Controlling “nukes” will require peoples’ power We must face the challenge of nuclear proliferation No nation has a “right” to possess nuclear weapons

- Global Sustainability through Global Law. . . . . . . . . . . . . 128 The population crisis is accelerating Overpopulation has a global solution Global government is needed to address the AIDS epidemic A solution to global warming is urgently needed

- World Democracy and the Global Energy Crisis . . . . . . . . . 144 Global government must play a key role in renewables Hydrogen is an option—especially with a global approach A global government could mount an “Energy Marshall Plan” The role of conservation is critical A global solution to the energy crisis is needed

10. Overcoming Poverty through Global Government . . . . . . . . 155 The world must address the preventable problems of the poor Fighting global poverty is in everyone’s interest Global government is the only effective solution to global poverty

11. The Need to Rethink Borders . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 162 Migration and trade issues need a global solution The EU is setting the stage for more open borders The world is localizing and globalizing at the same time

12. The Critical Role of the US in Global Governance. . . . . . . . 172 America is currently not ready to lead the world The world community is standing up to the US The US is currently an obstacle to global environmental protection

13. How Do Corporations Influence the World? . . . . . . . . . . . 184 The military-industrial complex unduly influences intern’l relations Large corporations win friends and influence people—with money Economic globalization cuts both ways

PART III Global Activism for a New Epoch

14. The Inner Revolution for World Government . . . . . . . . Young people are ready for global patriotism Cultural lines are softening in an interconnected world World government will liberate the inner life

Separation of “church” and state is needed at the global level

15. Focusing the Progressive Movement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Appendix A: Key Organizations and Websites in the

. . 193

. . 203

Global Governance Movement. . . . . . . . . . Appendix B: “Deck Chairs on the Titanic” by Tad Daley, Ph.D. Appendix C: “The World Federalist Movement: A Short History”

by Joseph Baratta, Ph.D . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 224 Notes …………………………239 Bibliography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 247 Index…………………………251

xiii

..211 . . 218

Preface

We have it in our power to begin the world over again.

—Thomas Paine

Common Sense 1776

This book is an introduction to the greatest political transformation in history—the democratic revolution to create enforceable global law.

This epochal change in human affairs will put an end, once and for all, to the war system that is the greatest scourge facing humankind.

In this revolution, ordinary people will take control of this planet from those who foment war and profit from war, and who permit environmental destruction.

This will be a movement of optimists and visionaries, those who are ready to seize the opportunity to reinvent our world, ready to leave behind the cynics whose only contribu- tion is to maintain the status quo.

In this movement, world peace is not a vague and utopian goal—but a practical, enduring peace that is achieved through world laws that are passed by a democratic world legislature, interpreted by world courts, and enforced by a global government that represents all of humanity, high and low, north and south, black and white.

We truly can create “the parliament of the world, the gov- ernment of mankind” as the English poet Tennyson propheti- cally envisioned in the nineteenth century. The time for this historic task is upon us, now, in the twenty-first century.

This global peace and justice movement is already well under way. Worldwide demonstrations like the historic “global day of protest” against the US invasion of Iraq on February 15, 2003 are just one sign.

xv

xvi One World Democracy

Yet something more than rejectionism is needed from our progressive leaders. These times require a positive and practical vision for how to solve international conflicts; how to relieve global poverty; and how to end the physical destruction of our precious planet.

We therefore ask you to imagine a world peace move- ment focused on making the United Nations, or some succes- sor, into a truly representative government for all humanity.

Imagine a global legislature or world parliament whose first order of business is the abolition of war.

Envision a world court whose routine work is to apply global law to individuals, rather than punishing entire nations for the crimes of their leaders.

Visualize a planetary bill of rights that is zealously guarded, and a constitutional balance of power that prevents excesses by any branch of the world government.

Reflect on the satisfaction of living peacefully under the rule of global law where there is less government, lower taxes,better distribution of resources, no nuclear weapons, open borders, less environmental destruction, no imperial domination, no military-industrial complex, more security, more justice for labor and minorities—and a global renaissance in the arts, science, religion, and culture.

And imagine yourself a part of this, the greatest political movement ever to occur.

We the people of planet earth are the sovereigns of our destiny; if we stand together, we can build a just and democratic government of humankind that will abolish war forever, and work together with all nations to solve the other pressing problems facing our fragile planet. It really can be that simple—and that exhilarating.

Preface xvii

This book is directed especially at progressives and visionary leaders in all walks of life who care deeply about global justice, reduction of poverty worldwide, and the protection of the planet’s environment—but especially those who are working for world peace.

In our view, today’s world peace movement is too often marked by a naive utopianism that confuses human nature with angelic nature. Angels can live in peace without law and government—but humans cannot. In our all-too-human world, peace without justice is an illusion—an uneasy truce until the next war comes along, such as the intractable Israeli- Palestinian conflict. Global justice, we argue, is simply not achievable without the establishment of law by an elected leg- islature in combination with judicial institutions that interpret and apply the law. And courts of law are almost useless with- out enforcement mechanisms—the notorious impotence of the UN being a case in point. Those who aspire for world peace really have no choice but to work for the achievement of enforceable global law.

“There is no peace without justice, no justice without law, and no law without government”—according to the formula of the United World Federalists of the late 1940s. The decades since then have only affirmed the truth of this old activist slogan. A great day is coming when the world’s peace movement and social justice progressives will once again embrace this crucial syllogism; and that is the day when we will become empowered to end war and ecocide. Only then will there be an end to the military dominance of America and a genuine solution to terrorism. Only then can we really tackle the daunting problems of global pollution and grinding poverty.

xviii

Let us use the twenty-first century to create the end of war—not the end of humankind. To abolish war we will need enforceable global law—the expansion of civilization to a planetary scale. This book invites you on a lifelong journey to the achievement of planetary peace and prosperity. Let’s get there by working to build one world democracy.

One World

A Progressive Vision for Enforceable Global Law

Democracy

Part I

Principles of Democratic Global Governance

1

The Peoples of the World Are Sovereign

Today we must develop federal structures on a global level. We need a system of enforceable world law—a democratic federal world government—to deal with world problems.

—Walter Cronkite

Imagine an old Star Trek series like this: Captain Kirk and crew are out exploring deep space, getting into quirky dramas on far-distant planets; meanwhile, back on earth, Kirk’s home planet is a war-torn cauldron of sovereign nation-states armed to the teeth. A dozen wars are going on at any one time, and thousands of children die of starvation daily. Its leading super- power is fighting a global war on terrorists, mounting comput- erized weapons in space, and standing by while global warming destroys the planet’s ecosystem.

Not exactly a suitable home port for a Captain Kirk.

Star Trek instead depicted an “Earth Federation” in our future—an advanced civilization ruled by a democratic global government. Pessimistic science fiction writers usually resort to the flipside scenario, some version of a nightmarish future dystopia in which humankind has failed to rise to the manifold challenges of war, conflict, and greed. They indulge in an

4 One World Democracy

imaginative extension of the current planetary anarchy that we read about in the newspaper every day.

Which portrayal will win out? This book is about the proposition that there really is no acceptable future without enforceable global laws that will outlaw war, redistribute resources, and control pollution. We will present the vision of a real-life “earth federation,” and we believe that today’s progressives must lead the worldwide grassroots campaign that will make it come true—before it’s too late. But can we dare to imagine a global democratic government evolving, even in our own time? Or must the whole world endure more deadly warfare, terrorism, and ecocide before we come to our senses? Our common foe is the destruction of the planet by the quick method of nuclear war or the slow method of environmental collapse. Let us soberly look to these common threats, and summon the courage to affirm the ideal of uniting all of humanity around a global social contract. It was the great scientist Albert Einstein who wrote: “The UN now, and world government eventually, must serve one single goal—the guarantee of the security, tranquility, and the welfare of all mankind.”

The ideal of “one world” was established in the 1940s

The ideal of a united human family began to dawn on masses of people, at least young Americans, in the great activist era of the 1960s. The first pictures of the earth from space were beamed back from the moon in 1969. The Apollo astronauts reported great epiphanies as they viewed the planet from deep space for the first time. The visionaries and antiwar activists of the sixties, and these fortunate astronauts, pictured planet earth as it really is: a unified whole, a global family

The Peoples of the World Are Sovereign 5

of humanity, a gorgeous sphere without the artificial borders that can lead to division and war.

Seen from a distance in space or time, our deadly internecine squabbles, our monstrous war system, and our inability to protect the global environment and feed the poor seem backward and childish indeed. In this book we will invite you to step back in your imagination, and envision our plan- et’s true destiny that lies beyond our current nationalistic prejudices—the earth as a politically unified sphere of diverse peoples who live in peace.

This vision of a unified humanity has been growing ever since the 1960s, and in recent years has found remarkable expression in a rugged, worldwide peace and justice move- ment. This movement comprises a key part of the progressive vanguard of the coming “one world democracy.” Probably its greatest public moment was the simultaneous demonstrations on February 15, 2003 in over forty cities worldwide by an estimated 30 million people opposed to the Iraq war.1 Another key element of this global progressive movement is the annual meetings of the World Social Forum. The WSF was created in 2001 to provide an open platform to discuss strategies of resistance to the prevailing model for globalization that gets presented each year at the annual World Economic Forum at Davos, Switzerland by large multinational corporations, national governments, the IMF (International Monetary Fund), the World Bank, and the WTO.

But as you will see in this book, a crucial element is still missing from these creative and potent expressions of protest and resistance: a positive program to end war and exploitation through enforceable global law and a federation of nations, including a world legislature. We call those activists who susbcribe to this approach “enlightened progressives.”

6 One World Democracy

We believe that such a vision of a great global democra- cy, ruled by just laws and based on the inherent sovereignty of the people of the world, could powerfully unify today’s pro- gressive activists. With a clear objective of making war illegal through the rule of enforceable global law, the antiwar move- ment will grow similar to the way the abolitionist movement grew to eliminate slavery in the US in the nineteenth century.

The roots of this vision are not just a matter of imagina- tion or science fiction. We need only backtrack a few decades from the antiwar movement of the ‘60s and revisit the “one world” ideals of the postwar generation of the late 1940s.

The narrative of the post-WWII peace movement and its various initiatives for “one world” through world federal gov- ernment is an inspiring story of noble ideals and courageous leadership. Very few of today’s progressive activists are aware that a vibrant world federalist movement dominated the scene in the US in the second half of the 1940s—long before the 1960s. This movement had its beginnings in that unsung generation of activists and thinkers of the post-war era who arose after the nuclear era was suddenly inaugurated in the mushroom ball at Hiroshima. Renowned writers and leaders such as philosopher Mortimer Adler, physicist Albert Einstein, Supreme Court Justice Owen Roberts, presidential candidate Henry Wallace, attorney Grenville Clark, educator Robert Hutchins, and journalist E.B. White led the way and set the tone for thousands of activists.

During that forgotten era, an activist group called the Student Federalists was considered the most progressive. The largest organization, the United World Federalists (UWF), formed in 1947 by the merger of five groups, once had over 50,000 members, with affiliates in almost every state and on scores of campuses. Declining after the disillusionment of the

The Peoples of the World Are Sovereign 7

Korean War, the UWF went through several changes until it reemerged in the 1960s under the leadership of Saturday Evening Post editor Norman Cousins. After a period of decline, it was resurrected as the World Federalist Association (WFA) in 1976, and was based for three decades in Washington D.C. The WFA recently changed its name to Citizens for Global Solutions (CGS), with a focus on legislation and UN reform. The formation of CGS left behind several important splinters, most notably the Democratic World Federalists, based in San Francisco, which is a new national organization more specifically dedicated to the goal of world federation. In chapter four we also review two other grassroots movements dedicated to global democracy.

To get a sense of what the earliest blossoming of the “one world” movement was like, here is one vivid story of the progressive activism from that era:

Garry Davis was a young professional actor and a former US air force pilot who had become disillusioned with war after personally participating in the fire-bombing of German civilian targets. Mulling over his war experience one day in late 1948, something profound rose up in him and moved him to act. He pulled together some money and flew to Paris, to the temporary United Nations headquarters then at Palais Chaillot. Appearing outside the palace before the press and a crowd of observers, he dramatically renounced his US citizenship, proclaiming himself a “citizen of the world.” His next move was to literally camp just outside the UN head- quarters on a small bit of space that he publicly declared to be “liberated world territory.”

Then, with the support of activists whom he had rallied to his cause, Davis conceived of another publicity-grabbing

8 One World Democracy

event. One day, he made bold to enter the UN’s General Assembly itself. He stood up and interrupted a session to present a dramatic plea for a genuine world government—that is, until he was seized by UN guards. But at that very moment an associate named Robert Sarrazac, a former lieutenant colonel in the French military, arose and finished Davis’ speech, saying, “We, the people, long for the peace which only a world order can give. The sovereign states which you repre- sent here are dividing us and bringing us to the abyss of war.” Sarrazac called on the astonished delegates to cease their national disputes and “raise a flag around which all men can gather, the flag of sovereignty of one government for the world.”

Inspired by Davis’ sensational activities, over 250,000 people from many nations registered as “world citizens” through his new organization in the months thereafter; each made their own personal declaration of world citizenship. Meanwhile, approximately 400 cities and towns throughout France, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, and India—in part following Garry Davis’ example—proclaimed themselves “mundialized,” (or world territory), in the next few years. The so-called mundialization movement, largely symbolic in nature, soon faded in the confusion of the Cold War, but the world citizens’ movement had now been launched.2

This incident colorfully illustrates the key concepts of sovereignty that underlie this introductory discussion of global government. The issues and questions involved here are profound: What is true sovereignty? Can there be a “flag of sovereignty of one government for the world,” as Davis and Sarrazac proclaimed, or was this a fanciful metaphor? Does the evolution of sovereignty end with nation-states? Do individuals have rights only as citizens of nations—but not as

The Peoples of the World Are Sovereign 9

citizens of the world? And what would it take to “mundialize” our world once again, only this time for good?

Peace always grows as sovereignty expands

To get at an answer, we must first ask what sovereignty actually is, and how and from whom it is derived. After the fall of Rome in the West, the term came to refer to the so-called divine right of kings to rule, a right of sovereignty that was believed to be conferred on the throne directly by God.

A great landmark was reached when King John of England was compelled to sign the Magna Carta in 1215, which established in principle that the king was not above the law, and that noblemen and ordinary Englishmen have distinct rights. Beginning in the sixteenth century in Europe, Renaissance and then Enlightenment thinkers began to demolish the intellectual foundations of the feudal concept of divine right. They reasoned that the source of sovereignty must ultimately derive from the people over whom kings once ruled, rather than being a set of rights conferred upon the people by the king.

Later theorists have held that sovereignty is inherent and inalienable in individual persons, and cannot as such be transferred to governments. They have argued that the people simply grant “powers of governing” to different levels of government when it is legitimate, or that dictators may tem- porarily usurp people’s innate sovereignty when government is illegitimate.

Generally speaking, all of these writers and legislators have established the enduring democratic truth that sover- eignty resides both in individual citizens and in the collective whole of all the people. And thus began the transfer of the

10 One World Democracy

power to rule from one person (or one class or one race) to all the people, and the simultaneous recognition that each citizen has the right to “life, liberty, and property”—not just the king, or the nobles, or the ruling classes. This earth-shaking conception of democracy soon became the motivating force that drove the American and French revolutions, inexorably leading humanity to the era of the modern democratic state. Democracy has expanded from these roots in Europe and the US and is now practiced in some form in over one hundred and twenty countries worldwide.

Here is our point: If sovereignty has its source in the peo- ple, and if the world has progressively moved in the direction of increasing democracy in recognition of that fact, then this concept must have an even greater destiny than we see today.

History records the fact that the definition of sovereign- ty has been broadening to encompass ever-larger concepts of human community—ever-more inclusive definitions of who “the people” are. Each such expansion—where limited by constitutional government—has brought peace and security and advances in human rights and liberty to more and more people.

In the most general sense, the evolution of sovereignty can be said to have begun with the primitive family; this was followed by consanguineous (blood-related) clans and tribes. Next came city-states and then warring city-states, such as ancient Greece during its fabled wars between Athens and Sparta, or China before it was unified in the Han Empire.

Much like the Han emperors in the East—and around the same period in world history—the Romans greatly extend- ed sovereignty in the West. Rome enjoyed an unprecedented era of peace known as Pax Romana (Roman Peace) that lasted from just before the time of Christ through the fourth

The Peoples of the World Are Sovereign 11

century, by incorporating once-sovereign and warring cities and states around the Mediterranean into an integrated whole. The Han Empire, as well as the later Tang and Ming periods in China, were also golden ages of high culture and civil peace. These blessings were conferred upon these peoples through the broadening of the sovereignty of the Chinese state over large regions.

History describes the ways in which the broad reach of these ancient empires did at times break down, causing retrogressions to intervening eras of warring states; this was witnessed after the fall of the Roman Empire as Europe fragmented into hundreds of warring sovereign entities in the “dark ages.” Similarly, after its own golden era of several cen- turies, the fall of the feudal Ottoman Empire in the nineteenth century led to the fragmentation of the Arab world that we see today.

Europe fared far better than the Islamic world in the transition to modern forms of sovereignty and democracy. The intervening era in Europe between feudal empire and modernity witnessed the slow formation of functionally sovereign nations. In the early modern era in the West, the first nation-states arose out of the warring feudal estates of medieval Europe, some later to become sea-faring empires. The Treaty of Westphalia of 1648 enshrined the concept of sovereign nation-states in Europe. Ever since this treaty, the general goal of war and diplomacy has been a “balance of power.”

Notable in this evolution were the formation of the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Italy—Europe’s great nations to this day. The frequently warring provinces of Burgundy, Brittany, and Normandy consolidated to form the nation of France in the fifteenth century. James I united

12 One World Democracy

Scotland and England early in the seventeenth century, ending centuries of egregious violence. The unification of Germany and Italy came much later. Europe has lapsed into continent- wide wars many times in the last few millennia, only to over- come this curse with the great success of the European Union (EU) that was effected in the late twentieth century. This political union of Europe is a regional democratic federation of nations that, perhaps more than anything else, presages the world federation to come.

Without exception, all such instances of the broadening and sharing of sovereignty have resulted in peace within the larger sovereign unit; retrogressions have usually led right back to outbreaks of fratricidal conflict.

Peace through broader sovereignty was also in evidence when the early Americans rejected their confederation of thirteen states—each with its own militia and sovereign power—and adopted a federation of states with a constitution that transferred the right to make war to a national federal government. The colonies won their independence from Britain in 1783, but struggled for five more years as a confed- eration of states in which each state retained sovereignty. Pennsylvania and Connecticut almost went to war over the treatment of Connecticut citizens who had settled in Pennsylvania. New York and New Jersey exchanged canon fire in New York Harbor over the issue of who would collect taxes from incoming boats. It was not until 1788, after the federal constitution was ratified, that the US was able to become the country we know it to be today, with the first Congress and President seated in 1789.

This act of federal union that led to the United States of America, and more recently the federation of the states of Europe that led to the EU, provide the best modern examples

The Peoples of the World Are Sovereign 13

of how a people’s decision to grant governing and law-making powers to larger and larger political entities confers the blessings of peace, law, and democracy to a wider territory. Europe, through the recent development of supranational law, has finally found peace after having been a killing field for centuries. Some thirty other countries around the world are based on some form of federations as well.

We’ve noted that sovereignty can be transferred not only upward but also downward, resulting in a new cycle of wars or the threat of war. In the US, this occurred in the American Civil War, a breakdown of national sovereignty that created two warring “sovereign” units. Something equally deadly occurred in the former Yugoslavia when its socialist federation was broken up into the smaller warring countries of Serbia/ Montenegro, Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Macedonia, and later Kosovo.

History teaches that any political union can be chal- lenged even after it has become well established; as with any government, a global government will require the continued vigilance of its members and of a vigorous world press if it is to endure and remain free of corruption.

The UN does not represent the sovereignty of humankind

We’ve seen that, throughout human history, sovereignty has been broadening to encompass an increasingly larger concept of community. We know that this increase in the recognition of the innate sovereign power of the people— based on the inalienable rights of individual citizens—has resulted in peace within the new and larger sovereign unit, and that this broader peace is maintained just to the extent that the rule of law and justice is maintained in that sovereign entity.

14 One World Democracy

The United Nations, of course, does not supply this wider recognition of sovereignty and law; it is not a true sov- ereign union. We can say categorically that the UN has failed to bring the peace and stability that the broadening of sover- eignty has been shown to confer upon humankind.

The UN is a relic of the post-WWII era, hindered in its work by a design similar to that of the failed American con- federation of states, which preceded the federal constitution of the US. Under the UN Charter, the right to make war is retained by individual nations; all actions are voluntary; and those agreements approved in the UN Security Council that are not vetoed by one of the five great powers are virtually unenforceable. A global arms race, dozens of bloody wars, and increasing global pollution mark the era of the confederation of nations known as the United Nations. Further, individual rights as such have no standing before the United Nations. Neither the innate sovereignty of the world’s people, nor the inherent human rights of persons, are reliably protected by the United Nations charter.

War and anarchy can be eliminated only when a new sov- ereign source of law is set up over and above the old clashing groups, creating an integrated whole and a higher source of law. The UN is not such a source of supranational law. The UN created a community of nations, and acts on the world stage as an agent for member nations.

But the challenge of our time is the quest to redefine our community as all of humanity. We currently see ourselves as Americans, Russians, or Chinese, but are we not truly one human community? Are we not unified by a common source, by the earth we all share, and by the desire for security and peace equally held by people all over the world? Global survival requires that we expand our loyalty to include not

The Peoples of the World Are Sovereign 15

just our family, city, state or province, and country, but to humanity and the planet as well—and that we affirm this with global law and democratic governance.

Our loyalty seems to have stopped with the nation, but

competitive nationalism is the greatest barrier to redefining our community as all humanity. Internally, nationalism is not neces- sarily an evil; it has been a unifying factor in many countries. But how long can humankind continue as two hundred separate countries, with two hundred armies engaged in an arms race? If nationhood continues to be the reigning form of sovereignty on this planet—and is kept in place through the legitimizing vehicle of the UN—then our future prospects are indeed stark.

It is often said that global government is overly idealistic and not a realistic solution to today’s problems. But it seems to us that the real dreamers are those who believe that today’s anarchic system of nationalism and war will bring a lasting peace. Anyone who thinks we can find peace by building more weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) should think again. Anyone who argues that the US can create security with a massive Pentagon budget need only bring to mind the scene of the Pentagon itself suffering a withering attack by a few clever terrorists. Those dreamers who think that peace results from an endless arms race will eventually return to square one: History proves over and over again that peace prevails only under the rule of government.

There is much to consider here. Many nations have built or can build weapons of mass destruction. This knowledge cannot be somehow erased by attacking these nations; this information is easily spread far and wide. The nuclear genie has long been out of the bottle. Who can put it back in, when each nation fears for its very survival? The UN has been almost

16 One World Democracy

powerless to stop nuclear proliferation. It is therefore only a matter of time until another Hitler, Stalin, or Saddam Hussein emerges to threaten the world with nuclear weapons or some other WMD. And probably nothing short of a reign of global justice based on enforceable global law could prevent terrorists from attacking on a more massive scale than they did on September 11, 2001. Global government may also be the only way to stop the dire threat of global warming—a problem all humans share equally. Multinational treaties and UN Security Council resolutions lack the force of law and simply cannot carry out these massive tasks.

With enlightened progressives all over the world in the lead, we must move beyond the obsolete concept of a community of nations and embrace the vision of the sover- eignty of the entire world’s people, or face a dismal future.

True sovereignty is personal and global

The “one-world guerilla theatre” of world government pioneer Garry Davis dramatized that there are ultimately only two permanent and functional levels of sovereignty: the free will of the individual person—the “citizen of the world”— and the collective sovereignty of humankind as a whole. Throughout this book, we will explore the proposition that these two forms of sovereignty are irreducible, each providing a kind of bookend on one side or the other of the concept of sovereignty.

We saw earlier that leaders in Davis’ generation pointed to the truth that only world government teamed with a global bill of individual rights could protect humanity in the nuclear age. But this achievement of the history of consciousness—so evident to the clearest thinkers after

The Peoples of the World Are Sovereign 17

WWII—was lost with the adoption of the UN charter and in the hard realities of the Cold War that descended upon the world in the early 1950s.

Courageous postwar progressives of the 1940s loudly proclaimed these great dual truths that the peoples of the world are the true sovereigns of this planet—not nation-states —and that each individual has universal rights. They produced the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 as a first edition of a proclamation of these principles. However, their leaders betrayed them, bequeathing to us the UN, an institution that was unable to prevent the devastating Cold War arms race—and the dozens of wars that have disgraced and disfigured our planet since that time.

Nations retain their identity in a world federation

Sovereignty transcends, but it also includes; the evolution of sovereignty does not in the least obliterate the previous levels of sovereign power. The replacement of the UN with a world government does not mean the abolition of local, national, and regional governments—it entails the federation of intact national (or regional) governments into a global sovereign power. Initially, nations will transfer only their war- making powers to the central government, just as the thirteen American colonies surrendered their war-making authority to the federal government, while still retaining their state militias.

It should be clear from our account that intervening “sets” of human groupings will and must exist between the level of the individual person and the “superset” called world federation. As conservative thinkers going back to Edmund Burke have shown, a political order must take measures to preserve the integrity and healthy functioning of each level of

18 One World Democracy

the “scaffolding” of society that exists between the individual citizen and the state—in our case, between the two funda- mental levels of the person and the planetary state. This mandate includes respecting the needs and rights of such relatively sovereign units as the family, clan, tribe, province, and nation— recognizing that these evolve over time, even as the individual citizen and the planet-as-a-whole remain limits of the concept. (One can include such groupings as ethnicities, churches, political parties, labor unions, and professional associations in this list as well.)

But these transitional political and social entities are always temporary, always only of relative value in the evolution of sovereignty. What we are saying here is that vast empires, leagues of nations like the UN, nation-states, tribes, clans, and recent global contrivances such as the WTO and IMF—all organizations of power short of personhood and planethood are useful, but only insofar as they enhance the welfare and progress of the individual or of humankind as a whole.

Stated again, in the evolution of sovereignty, what are of ultimate value are the permanently enduring entities: the individual and the whole species. It was long ago pointed out by the philosopher John Stuart Mill that the purpose of political evolution is to foster the greatest good for the great- est number of all persons and for the greatest length of time. To the extent that the benefits of law and government are extended to larger and larger bodies of men and women in this way—just to that extent is there progress. If the scaffolding of any intervening and transitory level of sovereignty prevents this forward progress, then the people of the world have the sovereign right to discard or reform it. Just as Thomas Jefferson asserted that the people have the right of revolution against tyranny, so also must a global right of rebellion become a

The Peoples of the World Are Sovereign 19

new rallying call for progressives longing for a peaceful and just world. As with the Founding Fathers of the United States, today’s enlightened progressives will inevitably turn to the federal idea to replace our obsolete United Nations confederation.

But none of this requires that nationhood as such will be destroyed; it only means that the “absolute sovereignty” of nationhood is discarded, as real nations (and all other human groupings) become integrated into a more just and lawful political order at the global level.

Sovereignty is legitimate political power—in action

Seen in another light, sovereignty is nothing but political power. It grows by organization (and almost always by military might), and it is maintained and validated by the quality of the justice dispensed to individual persons through law and government.

By our stated criteria, the progressive growth of the organization of political power is good and proper, for it tends to encompass ever-widening segments of the total of humankind, thereby lessening the possibility of war.

But our cursory study of world history also shows that this same growth of organization creates a problem at every intervening stage. Political organizations, be they tribes, cities, or nations, are usually reluctant to trade a portion of their sovereignty to gain the benefits of an expanded rule of law. People instinctively fear rule by “foreigners” whenever any federation of powers is contemplated. But as history shows, the benefits accruing from the extension of the rule of law outweigh the risk of tyranny at all levels of government.

By the same token, many people rightly fear global

20 One World Democracy

government because of the downside possibility that vicious minorities might gain control. It is possible, of course, for any government to become tyrannical. A good constitution that guarantees rights and a separation of powers does not carry a guarantee that courts will uphold the laws or that the execu- tive branch will enforce them. The constitution of the Soviet Union was in many ways a progressive document, but was generally ignored; the policies that Hitler pursued were considered legal under German law as it evolved under Nazism; in the US, Congresspersons of both parties voted the Bush administration’s Patriot Act into law. What do these dangers point to? In the end, the burden of freedom always falls on the true sovereigns, not on government bureaucrats and politicians who are always subject to the temptations of corruption; it is the citizens’ responsibility to make sure that government serves the needs of the people and is true to the democratic intent of its creators.

Yes, a global government could become tyrannical, but then any government or organization can become corrupt. Shall we therefore eliminate all government or all organiza- tions? Shall we fail to institute government where it is needed, narrowing our vision to the status quo? Shall we say that it makes sense to have local, state, and national governments, but that it would be wrong and dangerous to have a global government? What is it about the global level of government that changes this equation? These questions will be addressed as we go.

But one fact is obvious: Presently, if a foreign country attacks another country, the latter has no choice but to fight back, either alone or through a treaty alliance. When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the US had no choice but to defend

The Peoples of the World Are Sovereign 21

itself by declaring war and creating a giant war machine. If one country is determined to violate the supposed sovereign rights of another, the only way to stop the aggression is to go to war—risking the use of WMDs or even world war. Under a global government, such foreign invasions will be outlawed; all military forces come under the control of the world body insofar as they cross national borders, and global law, demo- cratically agreed upon and enforced by global marshals and a world police force, governs the actions of individual nations in global affairs.

In truth, living under a system of war and anarchy with WMDs readily available for use on the field of battle—that is the really frightening choice when it is compared with tyranny. Under a constitutional system of global government, political crimes will surely be committed, but they will be dealt with by the world police force and court system; a democratic world legislature will represent the eyes and ears of the world’s people; political parties at the global level will compete for power on the basis of the fruits of peace and prosperity that they offer. One wonders how this can be seen as inferior to relying on a war system that allows nation-states the unlimit- ed sovereign power to attack one another at will and permits corporations to plunder the global environment outside the rule of law.

There are great challenges at each step between the two enduring levels of the individual person and the final consum- mation of political growth—i.e., the federal government of all humankind, by all humankind, and for all humankind.

At the moment, our world is stalled in a quagmire of nationhood, held up by centuries of inertia from proceeding toward planethood. The problem facing us at this stage is the delusion of national sovereignty, especially when linked to the

22 One World Democracy

corrupting influences of war profiteering, religious fundamen- talism, and rapacious global banks and corporations.

The hard truth is this: The concept of the absolute sovereignty of the nation-state is the profound political problem of our time—it is a transitory form that has served its purpose. Nation-states were first created to ensure basic law and order within their boundaries, but today they can no longer claim to provide even the most basic protections. When we wake up each day with the fear that a repeat performance of a terrorist attack like that of 9/11 is imminent, then we need to realize that it is time to move to the next level of sovereignty.

Our forebears in the late 1940s knew that the nuclear age had brought about a sea change. The proliferation of weapons of mass destruction in a world of international anarchy has created an unprecedented set of dangers. The nation-state as a provider of security and protection is bankrupt. There is no state in the world that can now provide reliable security. When the state can no longer fulfill its basic purpose, then it is time for reform. Progressives should be the first to realize that people have a right of rebellion against the spurious notion of the absolute sovereignty of the nation-state. The people of the nations of the world must transfer their war-making powers to a world federation, based on the dual recognition of the sovereignty of all humankind and the intrinsic rights of all individuals—or face catastrophe. The global governance movement is not trying to build a utopia; rather, it is urgently trying to prevent worldwide disaster.

A federation of all humanity . . . would mean such a release and increase of human energy as to open up a new phase in human history.

—H.G. Wells

2

The Case for Global Law

World federalism is an idea that will not die. More and more people are coming to realize that peace must be more than an interlude if we are to survive; that peace is a product of law and order; that law is essential if the force of arms is not to rule the world.

—William O. Douglas

Former US Supreme Court Justice

Today’s enlightened progressives have an unprecedented opportunity. As advocates of democracy—as the global democ- rats of the future—we are in the best position to represent the great truth that the world’s people, and not the world’s nation-states, are the true sovereigns of this planet.

But we must also be magnanimous and include another radical perspective. Imagine that we have colleagues who are global libertarians, and they have formed their own global political party that one day will sit just across the aisle from us in the world legislature. They will insist that, alongside the people’s sovereignty, we must observe the equally important principle of individual accountability before global law. This principle, they will say, is based on the notion of the irreducible free-will sovereignty of the individual. Its corollary idea, they will probably maintain, is the central importance of creating a global constitution with a universal bill of rights that will protect the rights of individuals—including voting rights—in

24 One World Democracy

relation to the global sovereignty of all humankind for which we, the global democrats, are the primary advocates.

We’ve seen how progressives can be empowered in this futuristic work by tracing our lineage back to the “one world” generation of the 1940s. We believe it is incumbent upon today’s progressives to pick up this torch once again.

Leadership entails making the essentials clear. This chapter breaks out a key feature of the discussion of chapter one by asking how enlightened progressives can take the lead in offering the world’s people a choice:

The force of law versus the law of force.

Today’s progressives already fight the excesses of the American empire, but now we must perform double duty: We argue here that progressives must also cut through the illusions of “collective security” via multinational treaties or the actions of the Security Council within the United Nations. We must tell all who will listen that it is time to choose between enforceable global law based on democratic deliberation, or the law of force in a world of anarchy. And in doing so, enlightened progressives must carry out yet another feat: To win on a global platform, they will also need to hold the space for both sides of the concept of sovereignty: the hard-won notion of the collective sovereignty of the world’s people, and the equally essential truth of the rights and duties of the individual world citizen before global law.

A simple truth: Peace requires the rule of law

It is a truism that, through slow and painful evolution, the rule of law has progressed steadily over the centuries. The benefits of this process can be seen everywhere today, but of course only inside national borders. Especially noteworthy is

The Case for Global Law 25

the peace and social harmony that results when the rule of law is extended to large national federations such as those in Canada, India, the European Union, and the United States, where citizens do not worry about their states or provinces going to war against each other. Throughout the world, most countries are relatively civilized within their own borders by virtue of the rule of their own native laws, backed up by their own homeland police and defense forces as well as some system of justice through civil and criminal courts.

As a thought experiment, consider for a moment what the US would be like if the federal government and federal law were somehow removed, and each of its fifty states were rendered an independent country with its own president, cur- rency, and national laws. A traveler who was a New York state citizen would need a passport, for example, to go from New York to New Jersey. Businesspeople selling products across the former US territory would have to deal with fifty different currencies and fifty different versions of contract law. Each nation-state would need to have its own standing army, and some nations would surely produce and stockpile WMDs in addition to their conventional arms. Some “countries” would be more socialistic (let’s say Vermont, California, Massa- chusetts) while others might be ultra-capitalist (perhaps Texas, Oklahoma, and Utah) and even aggressive toward other nations. One can imagine how likely it would be that small wars would break out from time to time—or even large wars, as these nation-states band together in treaty alliances for “collective security.” Imagine, for example, that Colorado and Arizona were facing a serious drought and began to dispute with one another over water rights involving the use of the Colorado River for irrigation. Given the absence of federal law and courts, they would be forced to go to war to settle their

26 One World Democracy

dispute if negotiations did not work out. Neighboring states or “treaty allies” might find themselves joining one side or the other, jostling for advantage in the conflict. Before long the situation might degenerate into a conflagration, ending with a nuclear confrontation.

This may sound a bit absurd, but this scenario is not far from depicting the state of international relations today. Whenever and wherever the rule of force (and not the rule of law) applies, war becomes a legitimate option for settling disputes—and the preparation for wars of defense becomes a necessity.

Of course, individuals in a civilized society do not have the option of resorting to violence to settle their disputes; a monopoly on violence is reserved for the state in connection with law enforcement or due process of law. Vigilante justice, revenge killings, intrusive surveillance, undercover espionage, and in general taking the law into one’s own hands are illegal for individuals, but all this and much worse is accepted as normal between nation-states—especially the strongest ones. Individuals must follow laws and limit their behavior accord- ingly, but nations, lacking a sovereign authority above them, may act without restraint if they can get away with it.

One can see how the option of law versus force offers such a stark choice. Lasting peace comes only from order that is based on law backed by the enforcement power of demo- cratic government. That’s why enforceable law is the antidote to anarchy. The rule of law at the global level is the only means by which the human race will be able to establish peace. Such an enduring peace is qualitatively different from a “truce.” A truce is based on an uneasy balance of power that usually marks the interim between wars; whereas genuine peace is the

The Case for Global Law 27

presence of order and justice, produced by law, which is the product of representative government.

Hopefully, a stable peace based on global law will one day grace this world. The greatest planetary achievements in science, industry, human relations, and the arts must await those great times. The essential point is that these more advanced things are enabled by one very basic thing: peace and justice through the rule of law.

“Law,” the poet Mark Van Doren once explained, “is merely the thing that lets us live in peace with our neighbors without having to love them.” Enforceable law is not nearly as good a thing as spiritual consciousness or moral maturity, and it is certainly no substitute for personal spiritual growth. But without basic guarantees of security, humans can regress to the animal aggression that is in the biological heritage of our species. In a state of anarchy and war, we tend to forget about love and tolerance.

History provides proof that the rule of law is indispensa- ble for avoiding the spiral of violence and mistrust that anarchy always creates. Law is in fact the prerequisite for generating sufficient amounts of good will in daily life so that a society based on love, tolerance, and compassion may have a chance to evolve—as these things cannot be directly legislated. Love and law always seem to arise together in this symbiotic fashion.

Thus it cannot be said enough: The only way to abolish war entirely is to establish the just rule of enforceable world law. If we can find the political will to achieve this great victory, the resulting reign of peace will in time produce the mutual trust and security between peoples and nations that could create a worldwide cultural and spiritual renaissance. This in turn would lay the basis for almost unimaginable

28 One World Democracy

levels of material and spiritual prosperity on a worldwide scale.

Legislators can quickly adapt global laws to global needs

The rule of law provides peace and stability, but it is also dynamic. The great advantage of representative government is that it permits orderly change and adaptation through deliberative assemblies of legislators, whereas a confederation of nations like the United Nations tends to be a guardian of the status quo. Without legislation and the ongoing interpretation of new laws by courts, law cannot and will not evolve. Without ever-improving applications of law as determined by democratic forums in touch with everyday needs of all sectors of society, social relations soon stagnate.

Meanwhile, social conditions continue along their own trajectory. Largely oblivious to the operations of government, life conditions continue to undergo epochal changes because of technological change or shifts in population. The result is in an ever-increasing lag between the functions of government and the realities on the ground.

This may explain why today’s international relations are in an advanced level of stagnation bordering on decadence. The UN reflected the needs of the world just after WWII, but it has not changed substantively since. The sad fact about the UN, according to Tad Daley, who led the Campaign for a New UN Charter, is that the UN was maladapted even for the post-WWII era:

Most of the architecture of the United Nations system was created at the end of World War II in a dramatically different international environment [from today]. Much of their design was directed at addressing the political and economic dislocations of the immediate postwar world. Indeed, the

The Case for Global Law 29

collective security mechanism at the heart of the UN Charter was arguably directed not even at the world of 1945, but the world of the 1930s. By far the central issue on the minds of the framers who met in San Francisco in April, May, and June of 1945 was “How do we prevent another Adolf Hitler?” But long-term issues like global environmental degradation are infinitely different from a Panzer blitzkrieg across the Polish border. We want to consider what kinds of global governance structures might be appropriate not for the world of the 1930s, but for the world of the twenty-first century.1

It is tragic indeed that today’s politicians have not responded to the imperative of adapting our international institutions to evolving global realities; but we believe a new generation of progressives can and will do what needs to be done.

We must distinguish between the causes and effects of anarchy

The tried and true solution to anarchy is just one thing: law and government. In all places and throughout history, government’s chief task in civil society is to first establish enforceable rules for resolving conflicts between individuals and groups without violence.

Why do cities or states within a nation no longer engage in warfare with each other? The answer has to do with relinquishing sovereignty.

As we have seen, war between groups of people organized into social units––tribes, cities, or nations—takes place when these groups exercise unrestricted sovereign power. When there is no higher authority to resolve conflicts on the basis of law and judicial processes, then chaos and war are the only options. War ceases the moment sovereign power is transferred to a larger or higher unit. War takes place when separate

30 One World Democracy

groups of equal sovereignty come into conflict. When sover- eignty was transferred to the nation, wars between cities and tribes ceased.

Peace is possible only when a new sovereign source of law is set up over and above the old clashing groups, creating an integrated whole and a higher source of law. Pollution across national boundaries will cease when enforceable global laws are passed to prevent it.

Armed with this understanding, we can stop confusing causes and effects and start treating the cause of war and in justice—not just the symptoms. The chief cause of war and terrorism is unlimited national sovereignty and the absence of global law—not the weapons these perpetrators might happen to use.

It is a positive step when citizens protest a particular war or rally for nuclear disarmament. But this type of action addresses only the symptoms of a war system based on unlim- ited national sovereignty. Today we must do away with the entire war system, not just with the weapons of war or any particular war.

In the final analysis, people resort to violence not because their race or nationality are prone to violence, not because they intrinsically lack love and decency in their hearts, not because they possess particular weapons, but because they are hopelessly frustrated by the fact that they have no legislative or judicial forum in which their grievances can be heard and adjudicated.

The cause of global warming is not simply carbon emis- sions and thoughtless, wanton drivers of sport utility vehicles; it is the lack of an enforceable global agreement to actually reduce these emissions. Rapacious corporations are not the cause of child labor in Indonesia; these corporations are able to run amuck in the developing world because of the lack of

The Case for Global Law 31

enforceable global laws that would outlaw child labor. The cause of sweatshop labor in Mexico is not simply the greed of some corporate CEO—we will always have greed in com- merce—but the lack of a global legislature that represents the interests of all people, including working people.

Legally speaking, the perpetrators of violent internat- ional conflict are the individuals issuing orders to attack and kill, not entire nations. Perpetrators of global pollution or labor exploitation are specific, identifiable individuals. We need to transform the peace and environmental movements into a powerful force for the creation of a cure for the true causes of war, pollution, and poverty—a global democratic government based on world law that applies to real individu- als. Law creates individual accountability—the very basis of a just society. The lack of individual accountability under enforceable law is the true cause of the global problems we face.

“International law” is a misnomer

Currently, nations have little binding power to control irresponsible behavior by other states—i.e., those individual heads of states who may engage in evils such as aggression, pol- lution, or nuclear proliferation. Today’s so-called system of international law, the foundation of our current system of treaties, is a sad and appalling misnomer.

Too long has our world witnessed the tragic results of the current system of treaties based on international law. No matter how significant a given treaty may seem, all such inter- national agreements are flawed in that they permit all the prerogatives of sovereignty to remain with the agreeing parties.

It cannot be said enough: International “law” is a myth.

32 One World Democracy

Under its supposed reign, parties are free to ignore with impunity the treaty obligations that are the basis of interna- tional law. They can do this because there is no global govern- ment with the power to hold these states accountable. But law is not truly law unless it is enforceable. Law proclaims that there is something that one must or must not do, with the understanding that failure to comply will result in specific consequences to the lawbreaker that are meted out by a legiti- mate government. Law requires the existence of government to enforce it; law will never exist without government until those far-distant utopian times when men and women are entirely self-governing.

Treaties have, in a sense, been helpful in laying the foun- dation for world law, but as any Native American knows, treaties do not protect the weaker party from the likelihood that the stronger side will not honor its end of the bargain when it sees an advantage. Since there is no third party to enforce the treaty, any party to a treaty can fail to live up to its promise with impunity. The Bush administration’s decision to pull out of the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty in order to proceed with its National Missile Defense System, and North Korea’s withdrawal from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, exemplify this problem. International law has evolved over the last century and in many ways has become more effective, but until the world forms a third-party enforcement mechanism, and until global government replaces the current system of treaties, international law will continue to be unen- forceable and ultimately ineffective.

A global system based on treaties is also weakened by the fact that only those nations who have ratified a treaty are obliged to abide by it. When a nation chooses not to sign a given treaty, or to unilaterally withdraw from a treaty, as many

The Case for Global Law 33

do, it obviously has no obligation to follow that particular agreement. When a system of world law replaces international law, a world legislature will pass laws that apply uniformly to the whole world—or at least to those countries that are members of the federation.

It is futile to try to establish world peace via the threat of nuclear terror, or by treaties, alliances, or an unstable balance of power between the largest states. If we are to create something that has never existed—enduring world peace and justice—we must be willing to build something that has never existed: democratic global government.

Global law is meaningful only if it is enforceable

We are living today under a flawed international system with nearly two hundred nations that are each virtually a law unto themselves. However, business and commerce must be conducted. The channels of trade and travel must be safe- guarded—somehow. Something must fill the vacuum that is created by the absence of a world government to enforce global law to keep the peace. And given the failure of the United Nations, that role will, by default, fall to the world’s largest military and economic powers and to an unenforceable, unreliable body of international treaties.

As progressives well know, in the last decade the US has rushed into the power vacuum caused by the end of the Cold War and the abiding weaknesses of the UN system. We are now faced with the prospect of unchecked military domina- tion of our planet by its sole remaining superpower. And this self-assumed American hegemonic role has great importance in the evolution of global law. It is perversely teaching us about one feature of the coming world government to which we have

34 One World Democracy

already alluded: In the absence of world law, firm enforcement of some other sort of international order is still needed in a dangerous world in which lanes of commerce must be kept open. In the absence of a democratic world government, a “new world order” will be provided by default by the world’s largest superpower.

In recent times, all US administrations, both Democratic and Republican, have dressed up their overseas interventions with a rhetoric that attributes their motives to the enforcement of the broader interests of the civilized world. One can clearly see the accent on “enforcement.” For example, in his ultima- tum speech to Saddam Hussein just before the US invasion of Iraq in March 2003, George W. Bush’s speechwriters dubbed our intervention as “enforcement of the just demands of the world.” Sadly, the Bush administration co-opted the language of global justice even as it perpetrated a unilateral, preemptive intervention on a sovereign nation. Rather than seize the dic- tator himself and apply some feature of existing international law against this one individual in a world court, the Americans were forced for the second time in slightly more than a decade to lead a war against an entire people. And this came after many years of US-led UN sanctions against Iraq that decimat- ed their economy while leaving a brutal dictator in power— precisely the opposite result of what could have been achieved by applying the principle of individual accountability!

Truly, our options remain stark: To restate, the essential choice is between the force of global law applied against indi- viduals in a governed world, or the law of force applied against whole countries in a world dominated by nation-states and a military superpower. America must decide whether it will be an obstacle to world law or a leader in the development of global democratic institutions. It is as simple as that.

The Case for Global Law 35

A complicated world like ours needs decisive enforce- ment of legitimate global law against individual lawbreakers, such as terrorists, drug traffickers, and dictators. But without it, high-minded phrases such as “the just demands of the world” and “international law” will become linguistic fodder for the reigning superpower. Propagandists in the US State Department (or leaders of any other superpower) will use such language to justify their own nationalistic and self-serving enforcement of illegitimate “laws” against entire countries. In the absence of a global institution representing the world’s people, which is empowered to enforce just laws of our own making, the US—or institutions it dominates such as the WTO, IMF, and World Bank—will always be happy to step in with its own interpretation of what is needed to keep the peace. In the new model that we propose in this book, law enforcement will instead be embedded in the context of a genuine global democracy—a global governing structure that represents the will and reflects the sovereignty of the world’s people.

Global law requires global courts of justice

Among the first planks of any global constitution will be the abolition of war between nations and the binding adjudi- cation of international disputes and criminal acts by legitimate world courts. The first imperative of world civilization is to outlaw murder of all kinds across national boundaries, and to use legitimate force to hold individual lawbreakers—and not entire nations like Iraq or Afghanistan—accountable before legitimate standards of world justice. And as the world gov- ernment applies global law against individuals, world courts will develop case law that interprets the global constitution

36 One World Democracy

and enhances our understanding of the human rights that will no doubt be enshrined in a global bill of rights. We as indi- viduals must follow laws and limit our behavior accordingly. In a civilized and governed world, nations too must follow laws that limit and control their behavior.

Oddly enough, back in early 2003, just as the Bush administration was descending into its role as arbiter and sole enforcer of a spurious “global law” of its own making, the true alternative to this scenario was quietly emerging and was briefly noted on the back pages of newspapers. The attack on Iraq was perhaps one of the worst events in international rela- tions; but what was arguably the best moment in global diplomatic history occurred in the very same month—the seating of the eighteen justices at the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague. This positive development was the mirror opposite of what Bush was foisting on the world.

The timing was remarkable. Although opposed at all points by the Bush administration, the ICC, as of March 11, 2003 was officially inaugurated in The Hague, where eleven men and seven women—selected from a list of the world’s finest jurists—were honored at a gala presided over by Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands. The inaugural ceremony was attended by foreign ministers and international diplomats from one hundred countries—and of course was totally absent of representatives from the United States.

We cite this example because the ICC is the progenitor of the coming system of genuine world courts. However, the coming world legislature, based on individual suffrage, has no precedent at the global level and will have to be created from scratch. Progressives who have achieved a global level of polit- ical consciousness should be in the forefront of this historic undertaking, which we discuss in more detail in the coming chapters.

The Case for Global Law 37

Enforceable world law is an idea whose time has come

Enforceable global law will not be achieved by revolu- tion; it will be an evolutionary accomplishment of human- kind.

We envision a gradual process that will be punctuated by a few sudden breakthroughs. For example, the breakthrough to the creation of the ICC—however flawed—put in place one more building block of progress. When the Security Council stood up for the UN Charter by confronting the US over its plan to invade Iraq, this too was a positive step in the direction of enforceable global law. Perhaps a provisional world legisla- ture will evolve that could pass advisory laws that would approximate an expression of the sovereignty of the world’s people. The accumulation of many small victories of this sort will eventually lead to a transformation in global governance.

At the moment, however, the momentum of forward progress is too slow. Global civilization is in an accelerating state of change, but the evolution of international law is stag- nant—frozen like a deer in the headlights of progress. Nuclear weapons and WMDs have spread everywhere, the environ- ment is collapsing, and economic globalization is rapidly over- taking the planet, but our political institutions and especially the United Nations are far behind in their adaptation.

Conditions are ripe for change. The great goal of the abo- lition of war stands just before us, representing the pinnacle of the advancement of civilization through the force of law. Outlawing war will allow a vast shift of resources from the war system to the betterment of the human condition. This prece- dent will lead to global environmental protection and other just laws. The Pax Romana of the Roman empire and the peace now enjoyed within the United States illustrate advantages of

38 One World Democracy

coming together to form a union. When war is replaced by law, greatness becomes possible.

We are a link in the human chain of evolution. We owe a debt to those who came before us, some of whom gave their lives for the blessings we now enjoy. We need to be a strong link in the chain between this legacy and the immediate future. It is our opportunity to be either a generation of glory or a generation of shame. Let it not be said that we were the link that broke. Let it instead be celebrated that we were the generation that found the courage to face this truth: Enforceable global law is the answer to global problems. As Harris Wofford, the founder in the 1940s of the Student Federalists, once said, we are engaged in “the revolution to establish politically the brotherhood of man.”

Our ideal is a world community of states which are based on the rule of law and which subordinate their foreign policy activities to law.

—Mikhail Gorbachev

3

From World Citizenship to World Democracy

I am a citizen, not of Athens or Greece, but of the world.

—Socrates

By virtue of physically inhabiting the same planet, human beings everywhere suffer in common from such mal- adies as nuclear proliferation, global warming, and the war sys- tem that forces every country to waste vast resources on arms. We live in a world in which oppressed groups lack legal recourse for their grievances in global courts; as a result, people everywhere are faced with the possibility of being caught up in a terrorist event or a war perpetrated by such oppressed groups. The horrors of 9/11 were not just limited to the US; images of these attacks sent emotional shockwaves to people in all countries, and terrorists soon thereafter mounted devastating attacks from Bali to Spain. In the wake of these tragedies, governments everywhere have had to institute unprecedented repressive measures in order to engage in the so-called “war on terrorism.” In addition, virtually everyone now shares in the vicissitudes of the global economy. International financial speculation has, for example, often caused grievous effects in unpredictable places—such as the collapse of the Mexican peso in 1995 and the so-called Asia meltdown in 1997. We have just begun to see how vulnerable all of us are in the face of our

40 One World Democracy